LOS ANGELES — When “Zoot Suit” first opened at the Mark Taper Forum in 1978, little about the production screamed hit. Much of the cast had scant acting experience. The story itself was a Brechtian take on a relatively obscure unsolved murder in 1942 Los Angeles; its climax involved a humiliating assault on a Latino man by racist United States servicemen. Just a decade earlier, its writer and director, Luis Valdez, was creating short skits for audiences of striking farmworkers in the fields of the Central Valley in California.

But audiences kept coming, and coming, selling out show after packed show. Fans came one week and returned with their families the next; Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead is said to have seen the play 22 times. After running for 11 months to sold-out audiences, first at the Taper and then at the Aquarius Theater in Hollywood, “Zoot Suit” moved to New York’s Winter Garden in 1979, where it became the first Chicano theatrical production on Broadway. Mr. Valdez then directed a feature-film version, which was released in 1982. “We had no idea any of this would happen, man,” he said. “It was like this huge explosion.”

On Tuesday, Jan. 31, a revival of “Zoot Suit” begins its run at the Taper, kicking off the theater’s 50th-anniversary season. A fantastical reimagining of the so-called Sleepy Lagoon murder case, in which 12 Latino youths were unjustly convicted by a biased judge, “Zoot Suit” features racist prosecutors and lovelorn kids, lively swing tunes and family squabbles. The infamous Zoot Suit riots, a series of racially motivated attacks against Mexican-American youths in the summer of 1943, figures in as well.

Jeanine Mason and Jeremy Ray Valdez during rehearsal for the revival of “Zoot Suit.” Credit Brad Torchia for The New York Times

Looming over it all is El Pachuco, a mythical trickster figure who can stop time and materialize wherever he pleases (think Prospero, but with a lot more panache), and “The Press,” a barking headline made flesh.

The show is both a homecoming and a reunion. Four decades after its world premiere, Mr. Valdez, who is 76, is back as director. Daniel Valdez (Luis’s brother) and Rose Portillo, who in 1978 portrayed Henry Reyna and Della Barrios, the young lovers at the heart of the play, this time around play Henry’s parents. “I got kind of choked up the first time I heard those words all over again,” Daniel Valdez said. “Coming back to it is a little like coming home.”

In the intervening years, Latino playwrights, from Cherrie Moraga to Luis Alfaro, have made their mark on American theater. Karen Zacarias started the Young Playwrights’ Theater in 1995; in 2003, Nilo Cruz became the first Latino to win a Pulitzer for drama. Then there’s Lin-Manuel Miranda. But no other Latino play has had the cultural impact of “Zoot Suit,” not to mention its influence on generations of subsequent Latino playwrights.

On a recent morning, the cast rehearsed a scene set in a Los Angeles dance hall. Several men wore high-waisted trousers, long watch chains dangling from their belts; the women sported T-shirts, tights and sneakers. The men were strutting, the women spinning, but when a rival gang arrived, colorful curses flew, then fists, and before you knew it, the switchblades were out. El Pachuco snapped his fingers, stopping time just as Henry was about to cut his rival’s throat. “That’s exactly what the play needs right now,” he said. “Two more Mexicans killing each other.”

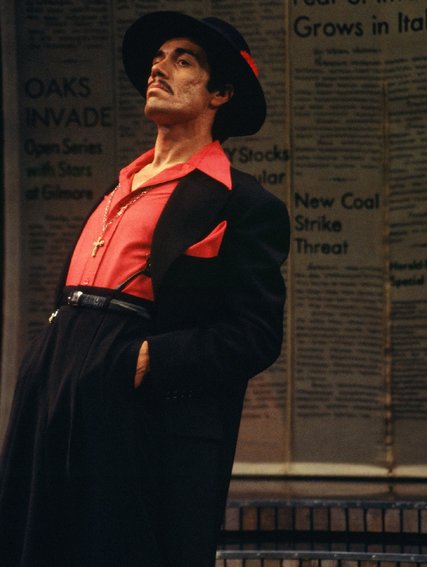

Edward James Olmos in the world premiere of “Zoot Suit” in 1978 at the Mark Taper Forum. Credit Jay Thompson, via Center Theater Group

The relevance of this scene in the Trump era isn’t lost on the cast and crew. Much of the play focuses on how Mexican-Americans are vilified in the United States as violent criminals and perpetual outsiders — “this ain’t your country,” El Pachuco tells Henry early on.

“That was part of the reason I felt that I had to be in this production,” said Demián Bichir, the Oscar-nominated actor who plays El Pachuco. “There couldn’t be a better opportunity for the arts to respond to so much nonsense and ignorance and stupidity.” (When not acting, Mr. Bichir, who is Mexican, is an American Civil Liberties Union celebrity ambassador for immigration rights.)

For Luis Valdez, mixing the political and the theatrical is nothing new. Dressed all in black, his voice a rich baritone, he recalled the years that led up to “Zoot Suit.” In 1965, he founded El Teatro Campesino, a theater troupe and “cultural arm” of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers. The group staged pro-union skits, which he wrote and directed, in halls and on the backs of flatbed trucks. After the troupe left the farm workers’ group in 1967, Mr. Valdez continued to write plays that examined the Chicano experience, including “Bandito!” and “I Don’t Have to Show You No Stinking Badges!”

“I call him the father of contemporary Chicano theater,” said Jorge Huerta, who wrote the book “Chicano Theater: Themes and Forms.” “Not only did he found the Teatro Campesino, the teatro inspired other teatros, an entire movement from the West Coast to the Midwest all the way to the Dakotas.”

Luis Valdez, who wrote and directed “Zoot Suit,” with the cast of the original production in 1978. Credit Jay Thompson, via Center Theater Group

In 1977, Mr. Valdez met with Gordon Davidson, who was the director of the Taper then, about creating something for its New Theater for Now series. He arrived clutching a pamphlet about the Sleepy Lagoon murder that he had gotten years earlier from David Sanchez, the founder of the pro-Chicano organization the Brown Berets. “He essentially gave me carte blanche,” he said.

Mr. Valdez set to work on the play, combining elements of Aztec mythology (Tezcatlipoca’s red-and-black colors, for example, mirror El Pachuco’s zoot suit); prison letters from the defendants culled from U.C.L.A. Library’s special collections department; and court transcripts. In one courtroom sequence from the 1982 film, a police officer testifies that pachucos have an “inborn” tendency for violence inherited from “the bloodthirsty Aztecs.”

“I took that from the transcripts,” Mr. Valdez said. “I didn’t invent that stuff. That wasn’t agitprop.”

“The Second Zoot Suit Riot begins,” an ad in a local newspaper declared in 1978. “That was probably hatched right here in this office,” Mr. Valdez laughed. “But there was a rush for tickets, so in that sense, it was a riot. A good riot. An artistic riot.”

The “Zoot Suit” director Luis Valdez, left, and the associate director, Kinan Valdez. Credit Brad Torchia for The New York Times

The play helped start the career of Edward James Olmos, who played El Pachuco in Los Angeles and on Broadway, as well as in the film. Mr. Valdez soon shifted his focus to movies as well — his 1987 Ritchie Valens biopic “La Bamba” was both a critical and box-office hit — but he’s still best known for “Zoot Suit,” which broke Los Angeles theater records for ticket sales during its first run.

The Taper, which also hosted the world premiere productions of “Angels in America” and “Children of a Lesser God,” hopes to create a similar buzz this time around. Univision and Hoy sponsored a party at the theater to celebrate the first day of ticket sales, complete with zoot-suited dancers and live swing music. The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach is lending art that will be on display in the theater lobby.

Strong sales have prompted the Taper to extend the show’s six-week run another week, through March 19; even after adding the additional shows, 35 high school groups remain on a waiting list to see special student matinees.

“We do 20-plus shows a year, and you can feel the excitement among the staff about having this show rehearse in our building,” said Michael Ritchie, artistic director of the Center Theater Group, which includes the Taper. “You can feel the buzz in the hallways.”

Those hallways aren’t far from many places, historic and infamous, brought to life in the play. Los Angeles’s Hall of Justice, where the young men were tried and convicted, is two blocks away; flash points of the riots erupted in the area. “Some of the riots actually took place very near where we’re rehearsing,” Daniel Valdez said. “Temple and Main, right down the street.”

A big difference between this production and the 1978 one is the level of the cast’s experience. “In those days, there weren’t many Latinos looking for a career in theater, so we were working with a lot of first-time actors,” Daniel Valdez added. “We had people who had never really been onstage. Now, watching the casting calls and the dance auditions, they’re absolutely amazing.”

The nationwide call drew 800 actors for 25 parts, and most cast members have backgrounds in film and TV. Mr. Bichir (“The Hateful Eight,” “Weeds”), a star in his native Mexico before coming to Los Angeles, was nominated for an Academy Award for his role in the 2011 film “A Better Life”; Jeanine Mason, a Cuban-American actor and dancer from Miami who plays Della, was the youngest competitor to win the Fox series “So You Think You Can Dance.”

Though the play was written in 1978 and set in 1942, Mr. Valdez feels its story is timeless, its themes part of an ever-repeating historical cycle. He traces lines from the Japanese-American internment camps to the Zoot Suit Riots, from Black Lives Matter to the vilification of Muslims. “And now the Mexicans are getting it again, thanks to Trump,” he said. “It’s like the closing of a complete circle.”

At a table reading between dance rehearsals, Mr. Bichir and Tom G. McMahon had questions for Mr. Valdez about how to tackle their roles as El Pachuco and the Press. In many ways, they’re more archetypes than people, jumping in and out of the action at will. The challenge, Mr. Valdez said, is finding the human in the trickster spirit. The play presents lots of similar challenges for audiences.

“My play has the same relationship to a normal realistic play as a zoot suit has to a normal suit,” Mr. Valdez said. “It’s different. The lengths are longer. There’s more fabric. But it’s very cool! And I think that’s part of the appeal.”

To view original post, click here.