By Luis Valdez

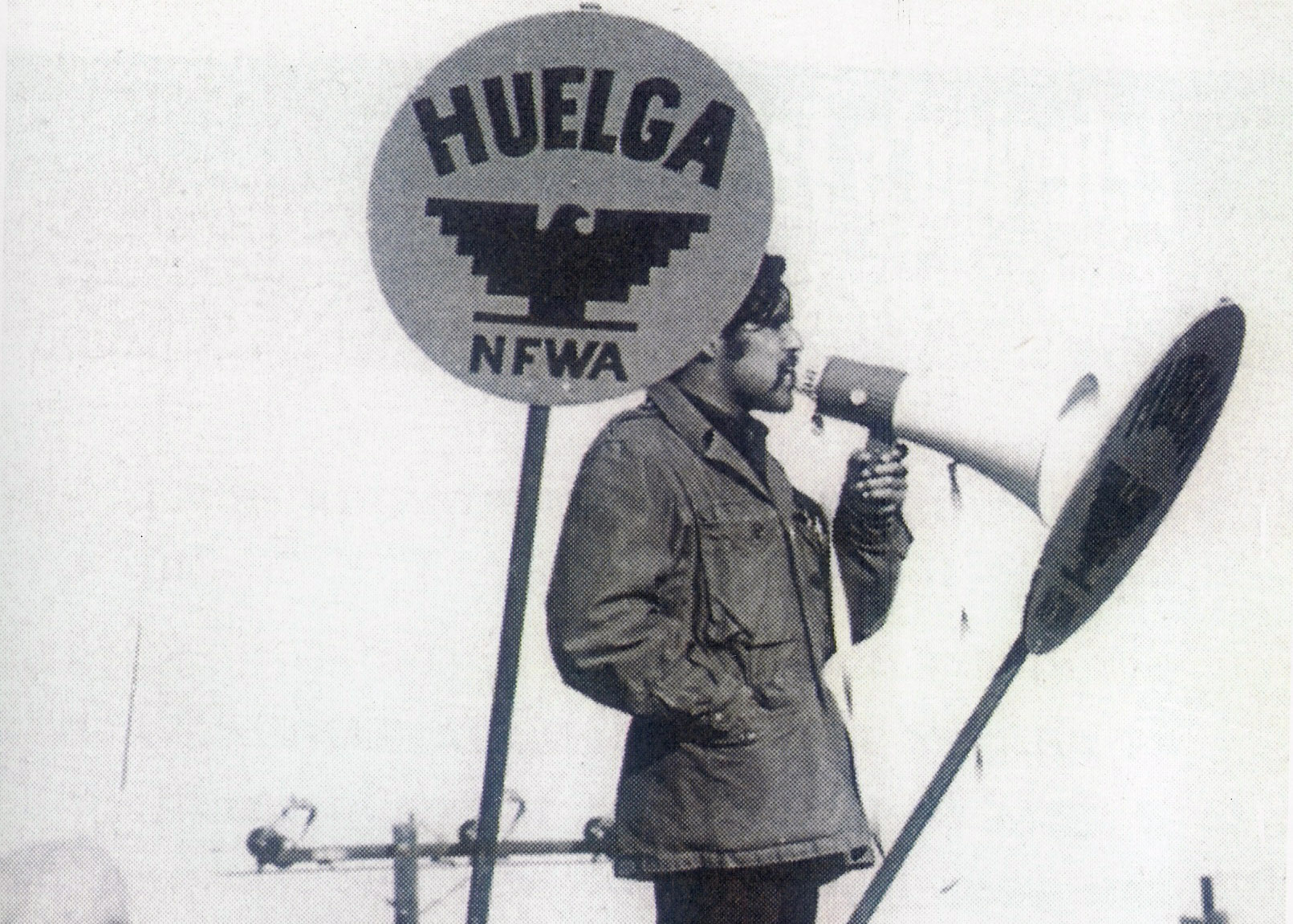

In the Spring of ’66, Senator Robert F. Kennedy flew into the Delano Airport in a small private plane, and gingerly asked an aide to remind him what he was doing there. It did not take him long to find his bearings. As a member of the Senate Subcommittee On Migratory Labor, he was in California for three days of hearings, one in Sacramento, another in San Francisco, the third in Delano. The Great Delano Grape Strike alias La Huelga had been raging for six months. The Senate Subcommittee was there to take testimony from both sides.

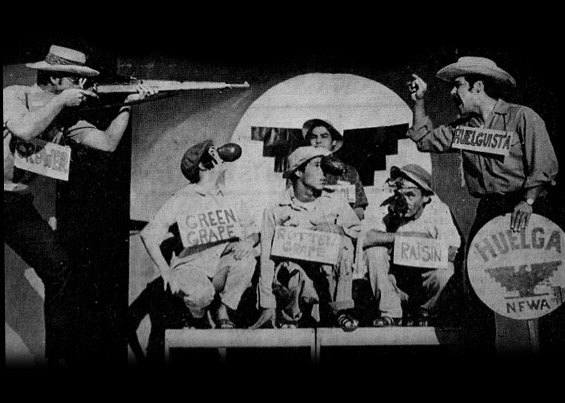

By this time, El Teatro Campesino, our Farm Workers Theatre- born on the picket lines four months before – had begun to earn its stripes among the rank and file performingat weekly strike meetings. Dolores Huerta gamely suggested that perhaps El Teatro should perform for the Committee as part of the testimony. Fred Ross and other members of the union leadership agreed, but Cesar decided a more appropriate time would be during lunch with the Senators.

Senator Robert Kennedy was absolutely heroic during the morning session, as he boldlychallenged old sheriff Lou Galyen for arresting our pickets “before they broke the law.” As the Committee broke for lunch recess, Senator Kennedy asserted: “Can I suggest that in the interim period of time. . . the sheriff and the district attorney read the Constitution of the United States?” The packed crowd of striking farm workers laughed, cheered and went wild. They had discovered a new champion in Washington D.C..

Under the glare of national media, Cesar and the Senator spent the lunch hour talking to reporters. The noontime performance never happened, but we took a rain check. For weeks the union had been preparing to embark on a 360 mile March to Sacramento, and El Teatro was put in charge of staging 25 consecutive nightly rallies on a flat bed truck. The burst of national media publicity from the Committee Hearings launched us on our pilgrimage the very next day. Bobby’s visit to Delano was only the beginning of a long political love affair between the Farm Workers Union and the Kennedys.

Of course, at least half of America had been in love with the Kennedys for ten years. I was a junior in high school, when a young Senator from Massachusetts caught my eye on the grainy black and white TV screen of my family’s 11 inch set. Jack Kennedy was attempting to become Adlai Stevenson’s running mate at the 1956 Democratic National Convention. He lost to Estes Kefauver, who looked old and stodgy to me compared to the young energetic Senator, but the die was cast for the future.

In 1960 that future arrived. Now a student at San Jose State College, I joined the “Viva Kennedy” campaign as a precinct worker in San José. I was an active member of MAPA (Mexican American Political Association), but being only 20, I was not allowed to vote in the election. I didn’t care. I fervently wanted to help elect Senator Jack Kennedy as the next President of the United States. As an Irish Catholic, he naturally appealed to Latinos. I was attracted because he was the first candidate “born in the 20th century.”

That Fall our Democratic Presidential nominee came to San José. I couldn’t get over how ruddy and healthy he looked as he spoke right outside the Civic Auditorium, his shock of sandy hair waving in the breeze. The leader of our local MAPA chapter presented him with a big black Mexican sombrero festooned with sequins. The massive crowd urged him to put it on. Ever the clever politician, Jack Kennedy demurred, but with keen Irish wit promised to wear the Charro hat on 5th Avenue in New York during the Saint Patrick’s Day parade. The crowd loved it. I eagerly shook his hand, as we all squeezed around him en masse for the obligatory, historic photo.

That Fall Senator Jack Kennedy was elected by the slimmest margin over Richard Nixon. A sense of euphoria nonetheless swept America’s baby boomers, as the new President and his beautiful wife Jackie occupied the White House with their daughter Caroline. The youthful “vigah” of the new administration was briefly celebrated with a rash of 50 mile hikes led by his younger brother Bobby. This was the first time I became aware of RFK. Next there were newsreel shots of the President playing touch football with his brothers at their compound at Hyannisport. The sophisticated charm of the happy Kennedys, and the irresistible mythological appeal of their large Irish American family, seemed to embody the American Dream.

Then came the sobering reality and deadly retinue of the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Martin Luther King, the Civil Rights struggle, and the first military advisors sent to Vietnam. JFK appointed RFK as the nation’s Attorney General. So Robert Kennedy single-handedly earned the undying hatred and consternation of his political enemies, investigating charges of corruption between the Mob and Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters. As history has now observed, “Camelot” was neither as chaste or free of blemish as it first appeared, nor as morally unsullied. It was alleged that the President’s father, patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy, had used his own underworld ties to cinch the election of his son Jack. Then – suddenly, there was Dallas.

On the morning of November 22, 1963, I was in the campus cafeteria at SJS, as a live radio broadcast was piped in over the speakers. The whole place fell into a hush, as we heard the terrible news. When word came that the President had been shot in the

head, a moan passed through the entire campus. All remaining classes were cancelled. The Kennedy assassination, followed soon afterward by dark suspicions that the CIA was behind it, radicalized my heart. I can only imagine what it did to his family.

When Senator Robert F. Kennedy came to Delano in the Spring of ’66, he was already a different public servant than he had been as Attorney General. Though the political murder of JFK had effectively shattered to bits the American Dream of the Kennedys, RFK carried on. Of course, unlike Jack, Bobby was not known for flamboyant quips and witty exchanges with the press corps. A tough, sinewy strength was lurking behind the shy smile and courageous demeanor. But there was something more. He was beginning to articulate a new sense of social justice in America from the bottom up.

Elected Senator from New York in ’65, RFK returned to Washington as heir apparent to the Kennedy legend and, even though no one admitted it, destined to make his own run for the White House. Yet he had changed. He was not only less cocky and truculent, but still raw and wounded by the trauma of the assassination. This is what made him newly sensitive to the plight of the racial minorities in America. As much as cynics may scoff at the notion, you could see the pain in his eyes. It was no coincidence that he began to champion the working class from Appalachia to Delano.

In the summer of ’67, when El Teatro Campesino embarked on its first national tour, one of the unforgettable highlights was our performance at the Capitol. Within the courtyard of the U.S. Senate Building in Washington D.C., our actos finally served as testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor, under the sponsorship of Senators Robert F. Kennedy of New York, Harrison Williams of New Jersey, Ralph Yarborough of Texas and Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts. Bobby cashed in our rain check for that cancelled luncheon performance in Delano.

On March 10, 1968, as Cesar Chavez ended his 25 day fast for nonviolence in Delano,Senator Robert Kennedy was at his side again for the ceremonial breaking of bread in Memorial Park and to offer his continued support for the farm workers’ cause. At the end of that same month, overwhelmed by the unceasing barrage of anti-Vietnam War protests, LBJ announced that he would not be the Democratic presidential candidate in the fall elections after all; making it fatally certain that RFK would be.

Less than a week later, on April 4th, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Bobby sadly broke the news to the crowd at one of his campaign rallies. A wave of bloody riots swept the nation in more than a hundred cities from coast to coast. The country seemed to be coming apart at the seams. Strangely, the psychopathology of the times was almost “business as usual” in a world at war with itself. . .

In the days preceding the California Primary Election on June 6, El Teatro Campesino joined Senator Kennedy on his whistle stop tour of the San Joaquin Valley in the final, climactic week of his Presidential campaign. By this time we felt like old comrades in arms, as the Senator personally introduced us. We sang Huelga songs before burgeoning crowds of farm workers. And for a brief shining moment, there was palpable hope that perhaps this time things would be different with Bobby in the White House.

On Primary night, we were invited to join Senator Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, together with Cesar and Dolores and other members of the United Farm Workers who worked tirelessly to bring in the crucial Latin vote. Other commitments prevented us from going to LA. But that night our friend Bobby was declared the winner of the California Primary, as he appeared on national TV, flushed with victory. Seeing Dolores Huerta at his side, the farm worker crowd at the Ambassador cheered deliriously. Then Senator Kennedy said “On to Chicago!” and left the podium, headed for the UFWA reception in the next ballroom by way of the kitchen.

Within seconds, the live TV announcer was declaring breaking news with astonishment. The unspeakable had just happened. The Senator had been shot! Gunned down as he made his way through the hotel kitchen pantry. The image of Robert Kennedy lying on the floor cradled in the arms of busboy Juan Romero was flashed around the world.

Lying on his back, the Senator characteristically asked Romero “Is everybody OK?” Juan replied “Yes, everybody’s OK.” Bobby then turned away, saying “Everything’s going to be OK.”

One witness immediately claimed a Mexican American had shot him. I couldn’t believe that. The shooter was caught and subdued on the spot by Roosevelt Grier, bodyguard for the Senator’s wife, Ethel. Taken into custody, the perpetrator was ultimately identified as Sirhan Sirhan, a recalcitrant Palestinian/Jordanian immigrant. In an excruciatingly ironic way that made more sense, though assassinating RFK would only add to the tragic toll in the Middle East. Unlike Jack again, Bobby did not die instantly. He lingered on over night, giving his family and millions of his friends, followers and survivors time to sorrowfully, bitterly, inevitably ponder more conspiracy theories. Then he was gone.

These days, as the 2016 Presidential campaign revs up, conjuring more putrid campaign film flam than ever, there’s more than one dubious politician to whom I’d love to say: I knew Robert Kennedy, Senator. Bobby Kennedy was a friend of mine. And believe me, you’re no RFK.

For ticket information on the RFK play at San Jose Stage Company, please click here.